ELEPHANT TOWER

The Tower Builders

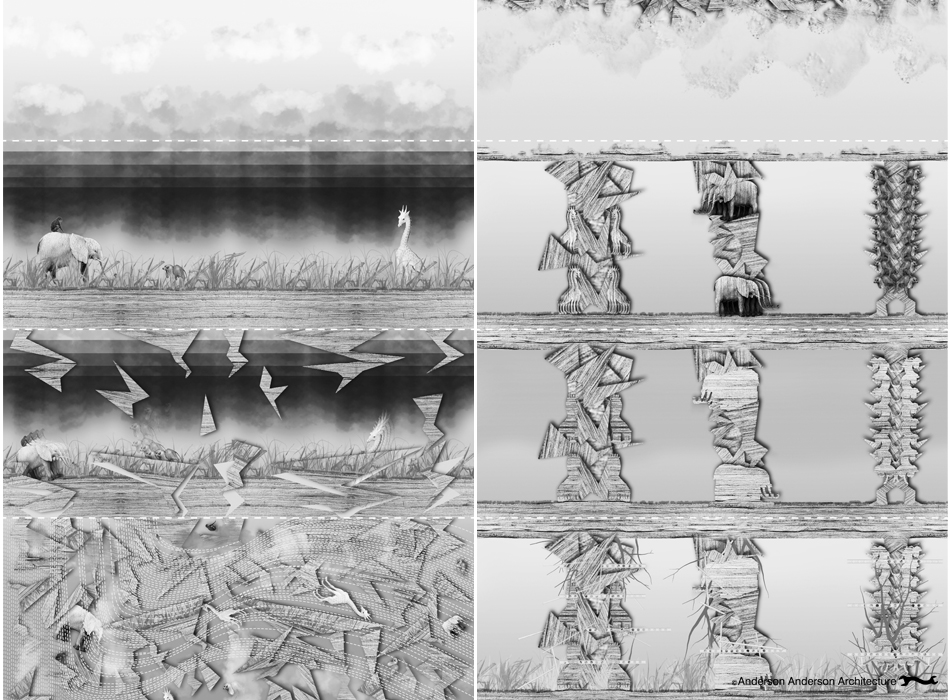

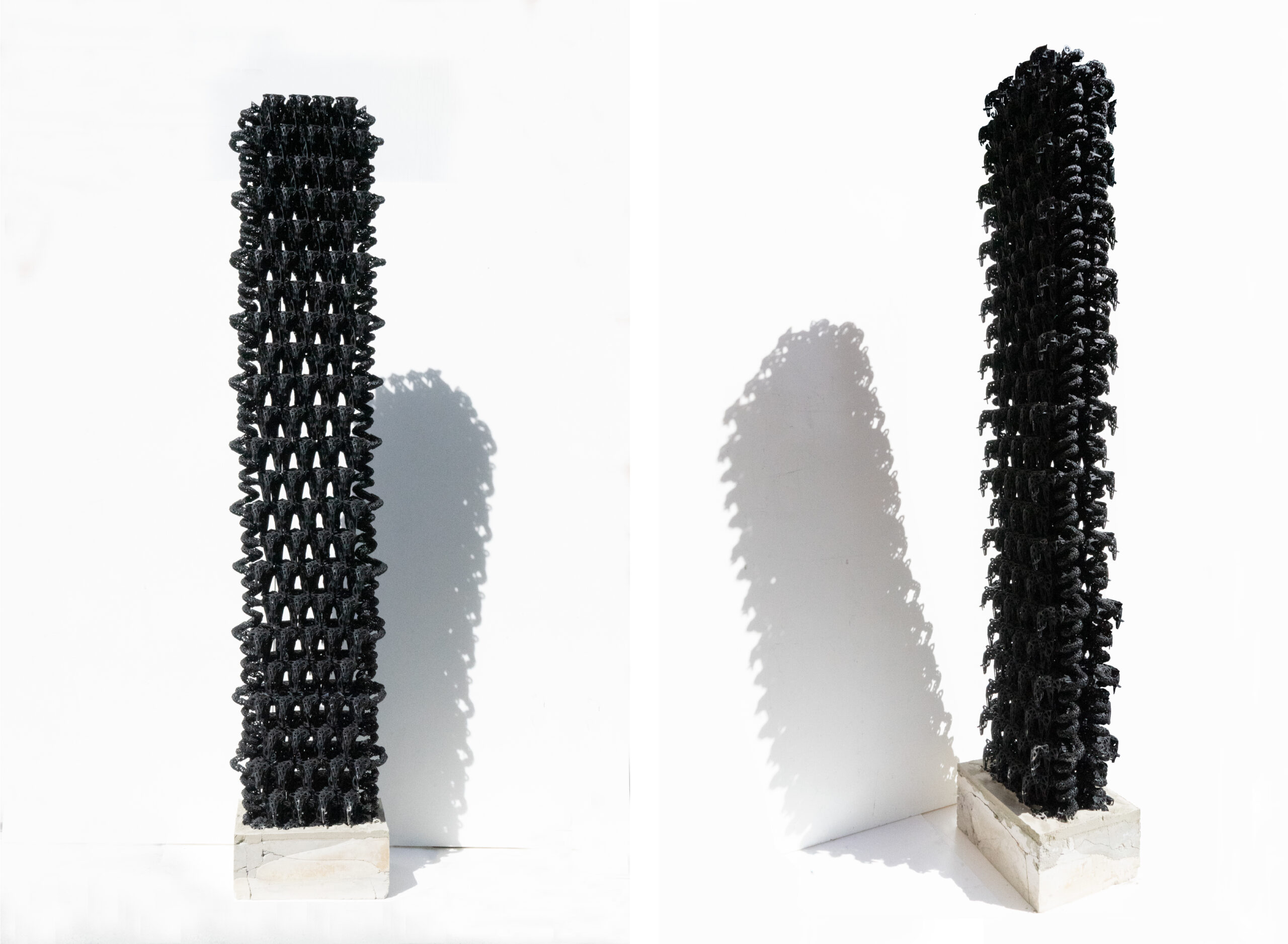

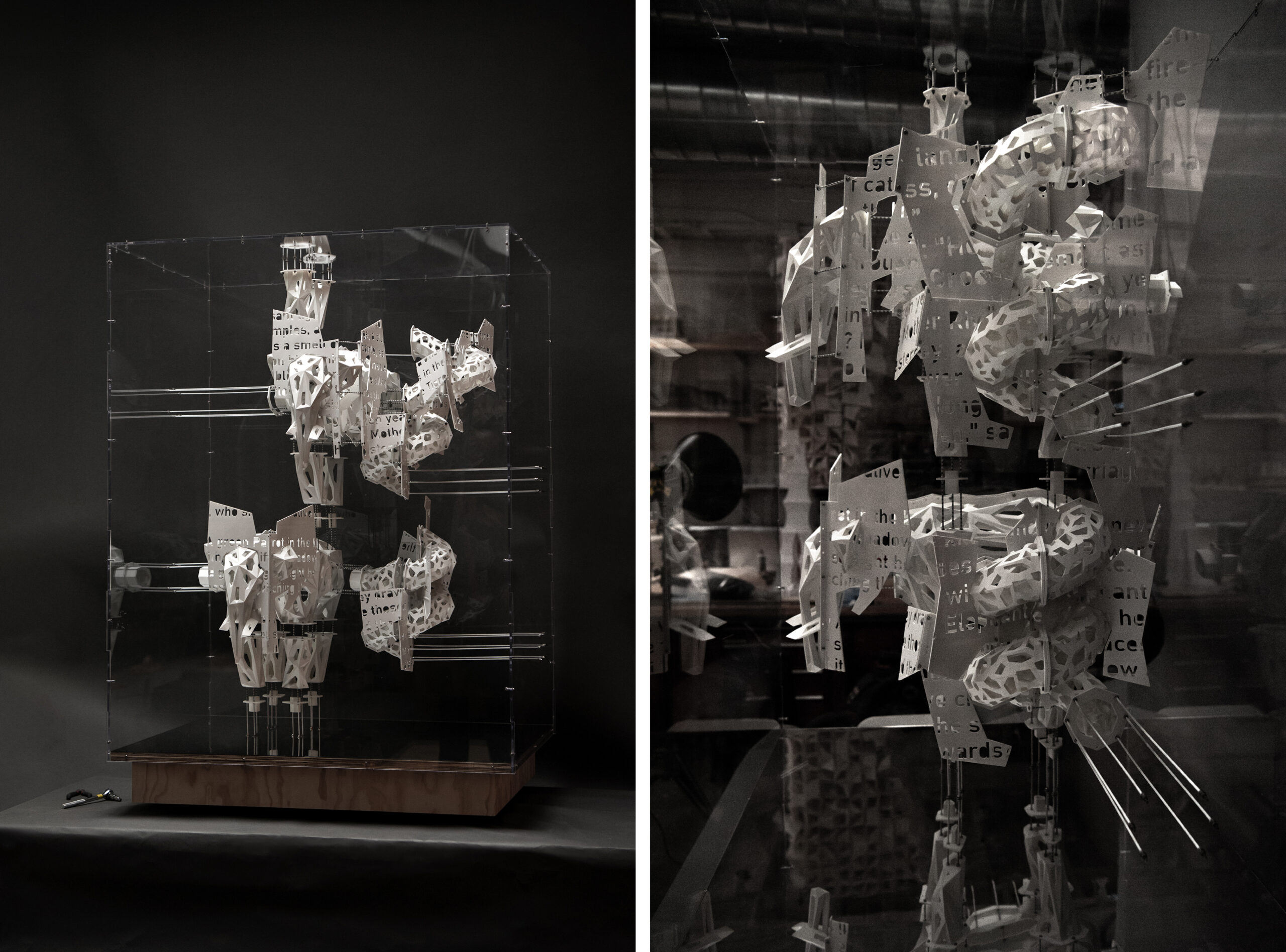

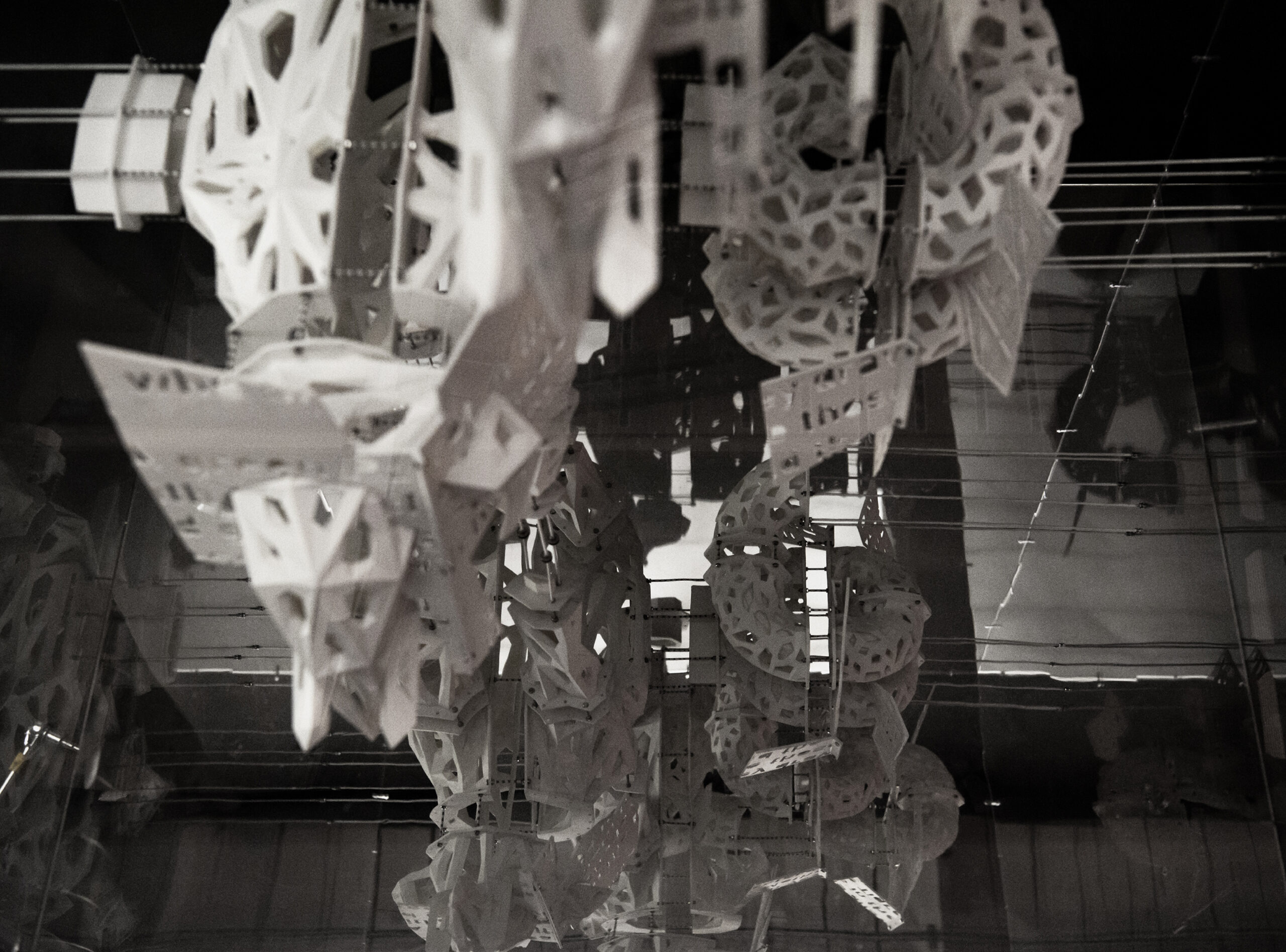

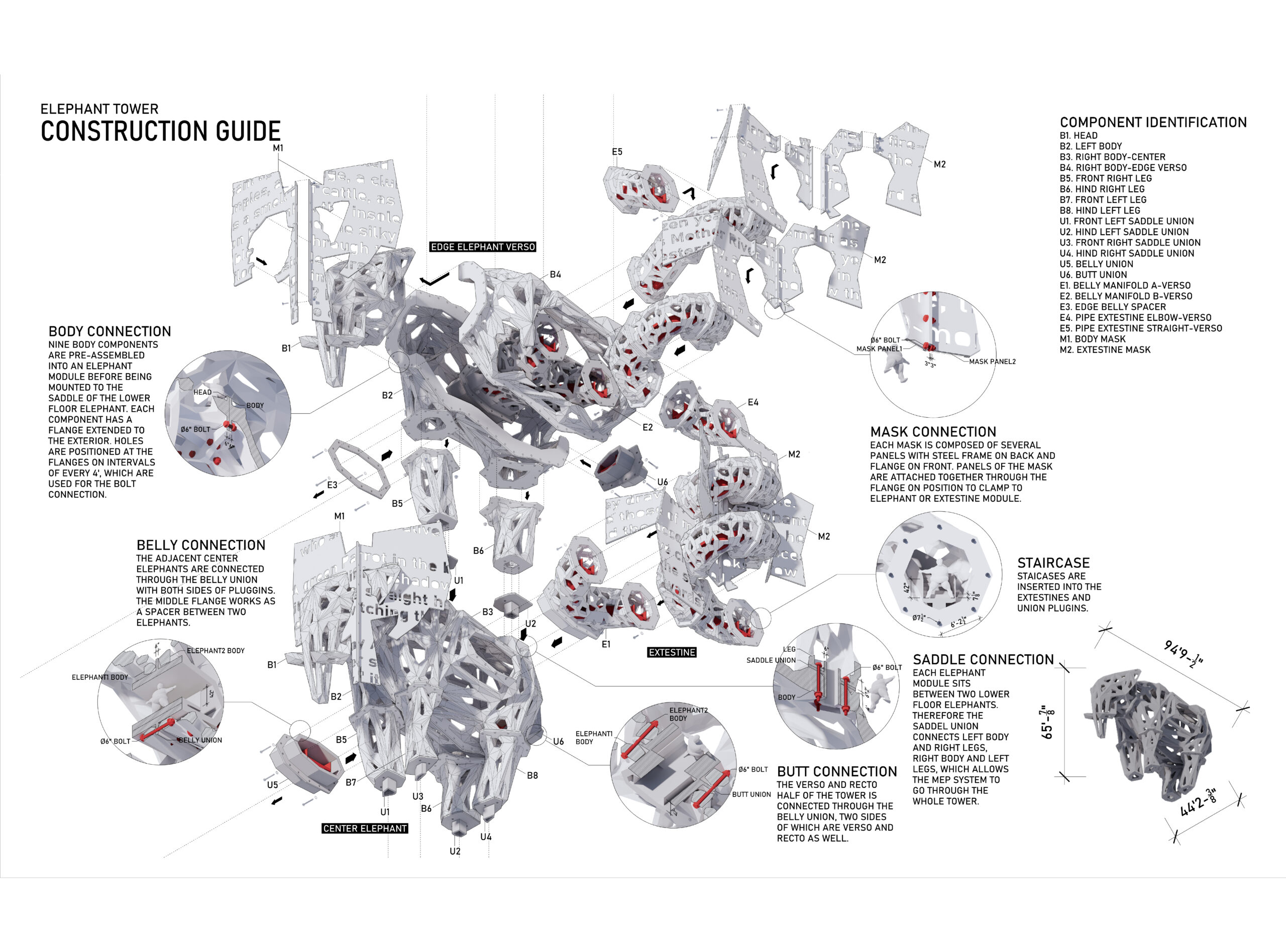

The Architect was far beyond any fear of snakes. He saw, after he had rubbed the water from his eyes, with an immense clearness, and trod, so it seemed to himself, with world-encompassing strides. Somewhere in the night of time he had built a tower—a tower that shot from the earth to illimitable heights in the sky; but now the Deluge threatened to sweep it away, to leave but flatness under heaven.

An incessant lightning, forked and blue, showed all that there was to be seen on this high patch of land in the flood—raw cliffs, ruined temples, a village, a clump of thorn, a clump of swaying creaking bamboos, and a grey gnarled baobab.

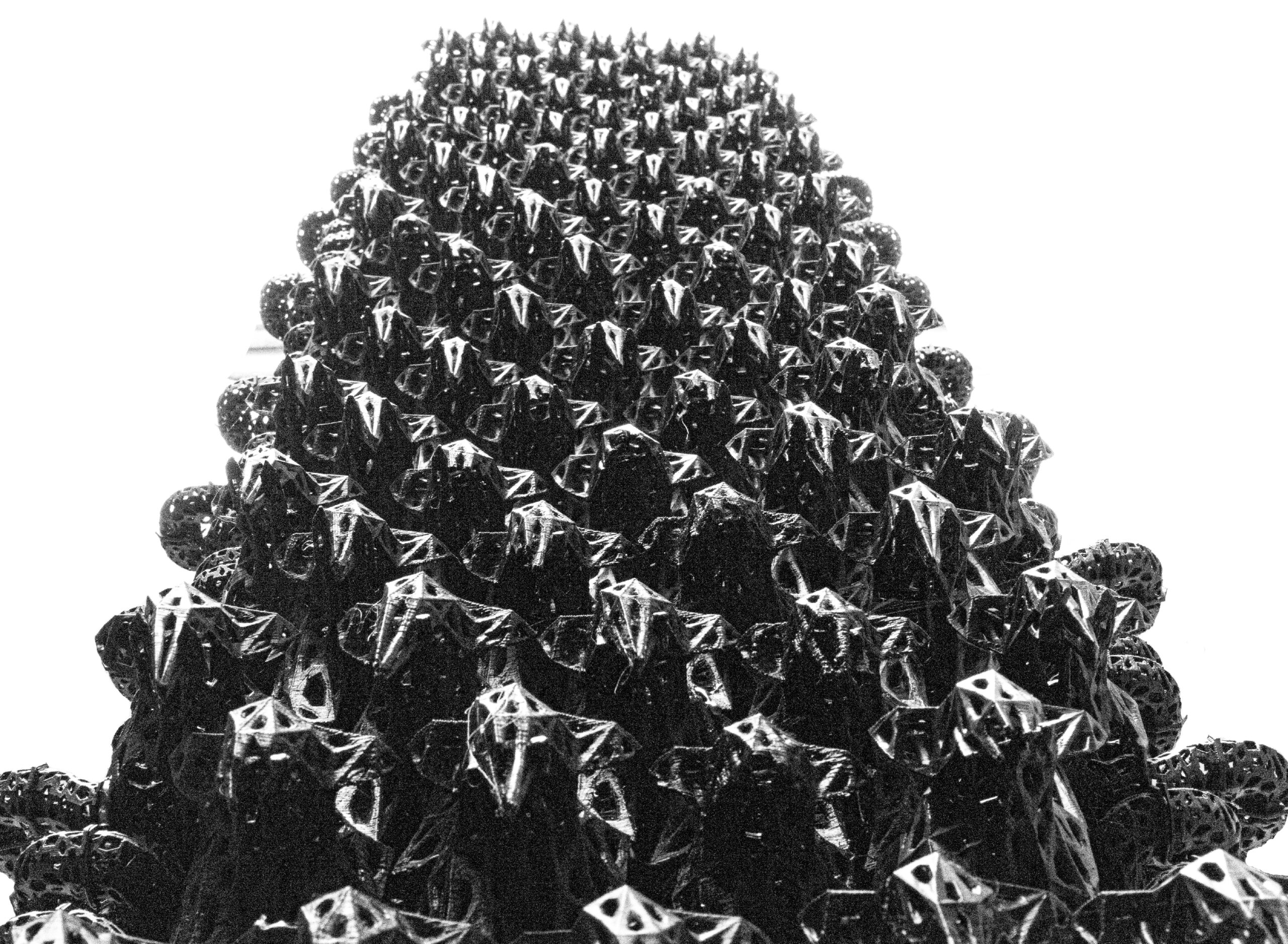

There was a smell of cattle, as a huge and dripping bull shouldered his way under the tree. The flashes revealed an intricate drawing on his flank, the insolence of head and hump, the luminous stag-like eyes, the brow crowned with a wreath of sodden marigold blooms, and the silky dewlap that almost swept the ground. There was a noise behind him of other beasts coming up from the flood-line through the thicket, a sound of heavy feet and deep breathing.

“Here be more beside ourselves,” said The Architect.

“Truly,” said the Engineer, thickly, “and no small ones.”

“What are they, then? I do not see clearly.”

“The Professors. Who else? Look!”

“Ah, true! The Professors surely—the Professors.” After the Flood, who should be alive in the land except the Professors that spoke it?

The Bull paused by the men, his head lowered to the damp earth. A green Parrot in the branches preened his wet wings and screamed against the thunder as the circle under the tree filled with the shifting shadows of beasts. There was a black Buck at the Bull’s heels- a Buck with a royal head, ebony back, silver belly, and gleaming straight horns. Beside him, her head bowed to the ground, the green eyes burning under the heavy brows, with restless tail switching the dead grass, paced a Tigress, full-bellied and deep-jowled.

The Bull crouched low, and there leaped from the darkness a monstrous gray Ape, who seated himself man-wise in their midst, and the rain spilled like jewels from the hair of his neck and shoulders. Other shadows came and went behind the circle. Then a hoarse bellow broke out from near the ground. “The flood lessens even now,” it cried. “Hour by hour the water falls, and their tower still stands!”

“My tower,” said The Architect to himself. “What have the Professors done with my tower?”

His eyes rolled in the darkness following the roar. A Crocodile—the blunt-nosed, ford-haunting Wraith of the River—draggled herself before the beasts, lashing furiously to right and left with her tail.

“They have made it too strong for me. In all this night I have only torn away a handful of reinforcement. The girders stand. The tower stands. The workers have chained my flood, and the river and wind are not free any more. Professors, take this yoke away! Give me clear water between bank and depth, clear air between earth and sky! It is I, Mother River, that speaks. The Justice of the Professors! Deal me the Justice of the Professors!”

“Did I not foretell it?” whispered the Engineer. “This is in truth a Congress of the Speakers. Now we know that all the world is dead, save you and I, sir.”

The Parrot screamed and fluttered again, and the Tigress, her ears flat to her head, snarled wickedly, while the island rang to the baying of hounds.

Somewhere in the shadow, a great trunk and gleaming tusks swayed to and fro, and a low gurgle broke the silence that followed on the snarl.

“We be here,” said a deep voice, “the Great Ones. One only and very many.”

“Give her the Justice of Speech.”

“Ye were still when they polluted my waters,” the great Crocodile bellowed. “Ye made no sign when my river was trapped between the walls. I had no help save my own strength, and that failed. What could I do? I have done everything. Finish it now, ye Others!”

“I brought the death; I rode the spotted sickness from hut to hut of their workmen, and yet they would not cease.” A nose-slitten, hide-worn Ass, lame, scissor-legged, and galled, limped forward. “I cast the death at them out of my nostrils, but they would not cease.”

“Little help! They fed me the corpses for a month, and I flung them out on my sand-bars, but their work went forward. Demons they are, and sons of demons! And ye left The River alone for their fire-carriages to make a mock of Justice on the tower-builders!”

The Bull turned the cud in his mouth and answered slowly: “If the Justice of the Professors caught all who made a mock of holy things there would be many dark altars in the land, Mother.”

“But this goes beyond a mock,” said the Tigress, darting forward a griping paw. “Thou knowest that they have defiled the River and the Sky. Surely there must come a Destroyer.”

The Buck made no movement as he answered: “How long has this evil been in construction?

“A dozen years, as men count years,” said the Crocodile, close pressed to the earth.

“Does Mother River die, then, in a few short years, that she is so anxious to see vengeance now? The deep sea was where she runs but yesterday, and to-morrow the sea shall cover her again as the Professors count that which men call time. Can any say that this their tower endures till to-morrow?” said the Buck.

There was a long hush, and in the clearing of the storm the full moon stood up above the dripping trees.

“Judge ye, then,” said Mother River, sullenly. “I have spoken my shame. The flood falls still. I can do no more.”

“For my own part “ – it was the voice of the great Ape -” it pleases me well to watch these men, remembering that I also builded no small tower in the world’s youth.”

“Surely they make these things to please their Professors,” said the Bull again.

A laugh ran round the circle.

“Not altogether,” the Elephant rolled forth. “It is for the profit of my fat money-lenders that worship me at each new year, when they draw my image at the head of the account-books. I, looking over their shoulders by lamplight, see that the names in the books are those of men in far places – for all the towns are drawn together by the fire-carriage, and the money comes and goes swiftly, and the account-books grow as fat as – myself.”

“They have changed the face of the land-which is my land. They have killed and made new towns on my banks,” said the Crocodile.

“It is but the shifting of a little dirt. Let the dirt dig in the dirt if it pleases the dirt,” answered the Elephant.

“But afterwards?” said the Tiger. “If we allow the tower to stand they will see that Mother River can avenge no insult, and they will fall away from her first, and later from us all, one by one. In the end, Elephant, we are all left with naked altars.”

–built upon a passage from Rudyard Kipling’s short story The Bridge Builders